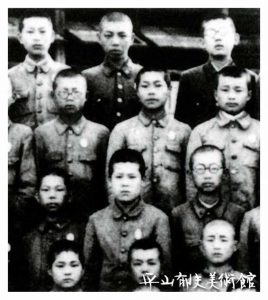

Childhood

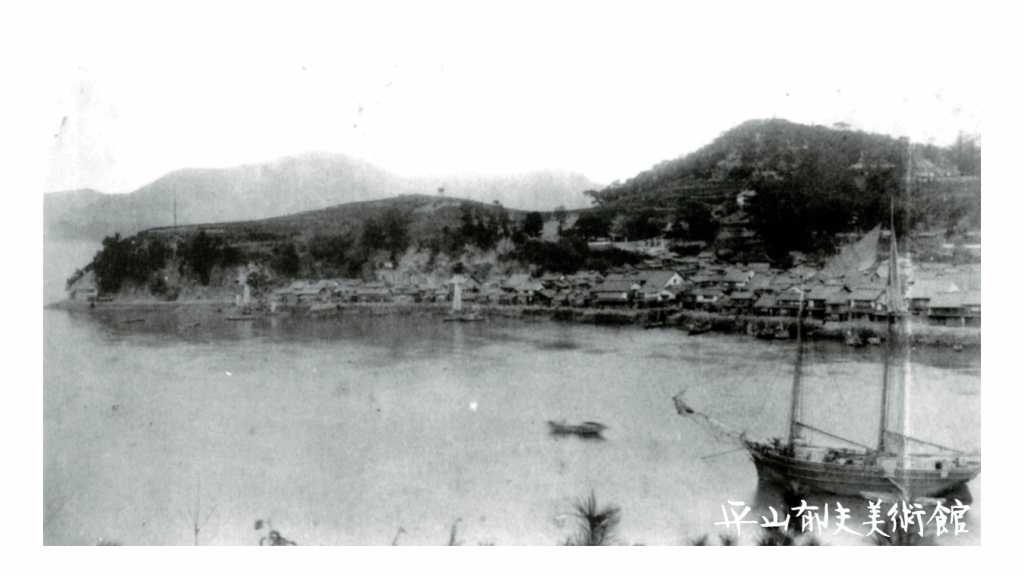

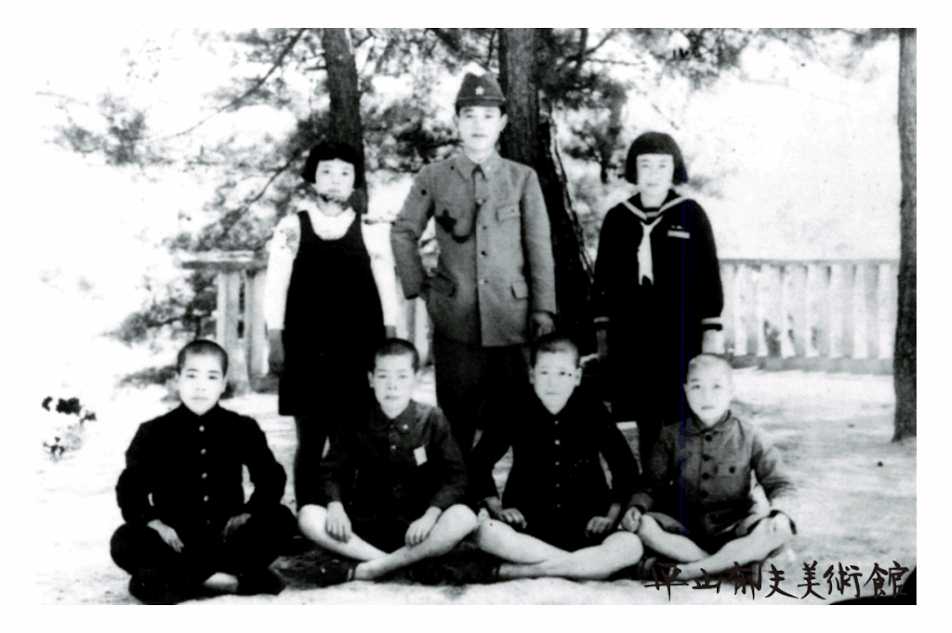

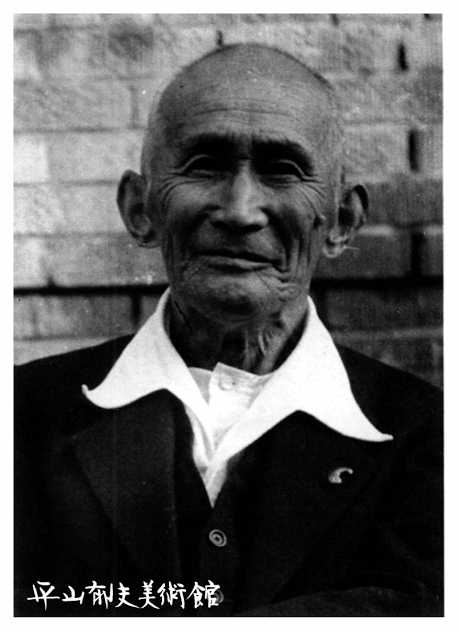

Ikuo Hirayama was born to father Mineichi, and mother Hisano of Setoda-cho, Toyota County, Hiroshima Prefecture (Ikuchi Island in present-day Setoda-cho, Onomichi City) and would be the second son in a family of 4 male and 5 female children on June 15, 1930. Ikuchi Island is blessed with the warm climate of the Seto Inland Sea and has many historic temples and shrines such as the three-story pagoda of the Kojoji Temple and Komyobo Temple, which is said to have been founded in the Nara Period. As a sensitive Ikuo and inquisitive boy, he spent his days romping about on the Island’s beaches gently lapped by ultramarine-hued surrounding waters.

This aesthetic sense and sensitivity nurtured by his beautiful natural environment and the deep affection of his faithful parents are very much alive in his later paintings.

01. Entrance into junior highschool and exposure to atomic bomb explosion

After graduating from the Setoda National Elementary School in March 1943, Hirayama entered the private Shudo Junior High School in Hiroshima City. With the Pacific War raging and the wartime regime in place at the time, he became sick and malnourished during residency at the dormitory and moved to a boarding house after his second year summer break. Painting was his only diversion from the hunger and loneliness of dormitory life. A program for wartime mobilization of students for labor service was set up in 1944. In spite of his poor health, he volunteered to work at the arsenal of the Hiroshima Army in Hiroshima City starting in July 1945.

On August 6, Ikuo Hirayama was working in the lumber depository outside the cabin. He was alone, looking at the clear sky after 8 am roll call. He noticed a white parachute falling from the sky and as he was going to enter the cabin to notify his fellow workers of the falling of the strange object, he noticed a large flash of light from behind. It was the explosion of the A-bomb. The shed was located a little less than 4 km away from the center of the explosion. He promptly returned to the dormitory, which was located a little less than 2 km away from the explosion epicenter to observe the situation from the foot of the Hijiyama Bridge. Witnessing this image of living hell, he quickly made plans to escape from Hiroshima to return to his parents’ home the next morning.

This experience as a 15-year-old junior high school student would remain with him for the rest of his life and served as inspiration for his later paintings depicting the life of Buddha including “Transmission of Buddhism” and a series of Silk Road paintings. You can see that his works, which are based on his junior high school days experiences, at the Hirayama Ikuo Museum of Art.

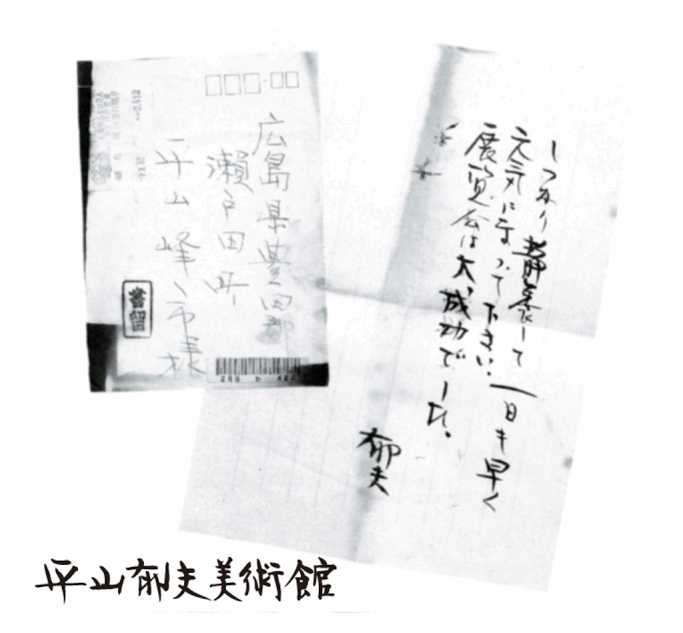

Partly because he had been sick in bed for a while after the exposure to the atomic bomb explosion, he transferred to the Hiroshima Prefectural Tadanoumi Junior High School in November after the war.

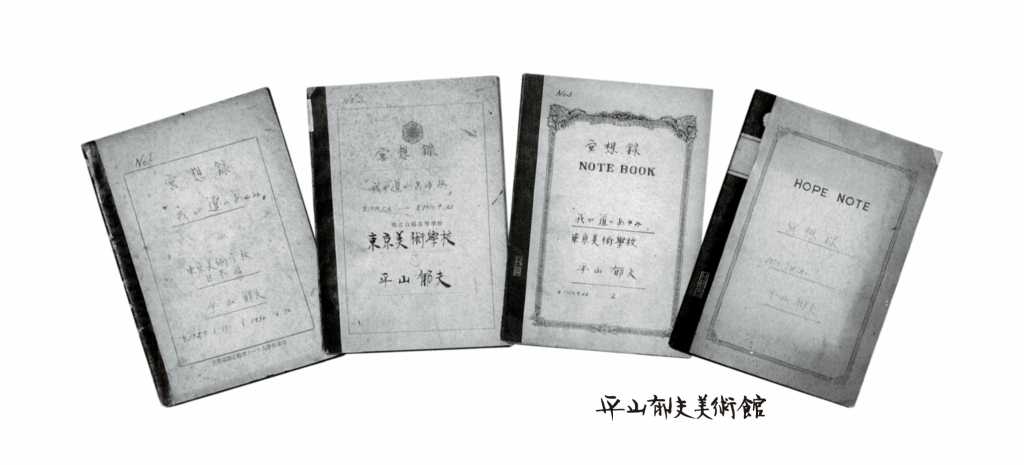

02. Enrolling in the Tokyo School of Fine Arts

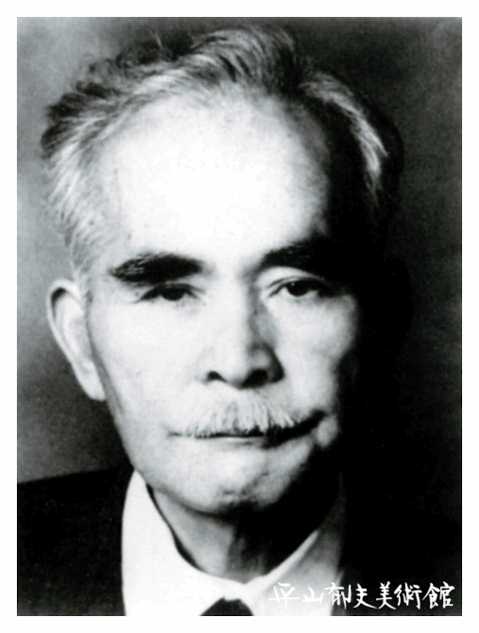

After completing studies at Tadanoumi Junior High School in four years, he entered a preparatory course in the Department of Japanese Painting at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (present-day Tokyo University of the Arts). He chose this school following the emphatic recommendations of his great-uncle (grandmother’s elder brother), Nanzan Shimizu, an engraver by profession. Hirayama lived with Nanzan and was instructed in art theory and painter preparedness, etc. by Nanzan.

At art school, he was mentored by professors such as Kokei Kobayashi and Yukihiko Yasuda. Upon graduation in 1952, he became junior assistant of a newly-appointed professor, Seison Maeda, at the renowned Tokyo University of the Arts and later became an assistant.

Those years of his life may seem idyllic. However, later in life, he mentioned feeling inadequate at the time because he was the youngest in his grade and had not especially studied painting techniques. Furthermore, partly because of the generally pessimistic atmosphere of the time epitomized by the “destruction of Japanese art” theory that was in vogue, at one time he even thought of abandoning the hope of becoming a painter and aspired to become a researcher instead. However, he recovered his confidence after he was kindly persuaded by Shinichi Tani, a professor of Japanese art history and graduated with second highest standing in his level in 1952, and his works received wide acclaim and sold well. (It’s interesting to note here that Michiko Matsuyama, who later became his wife, was the top student that year.)

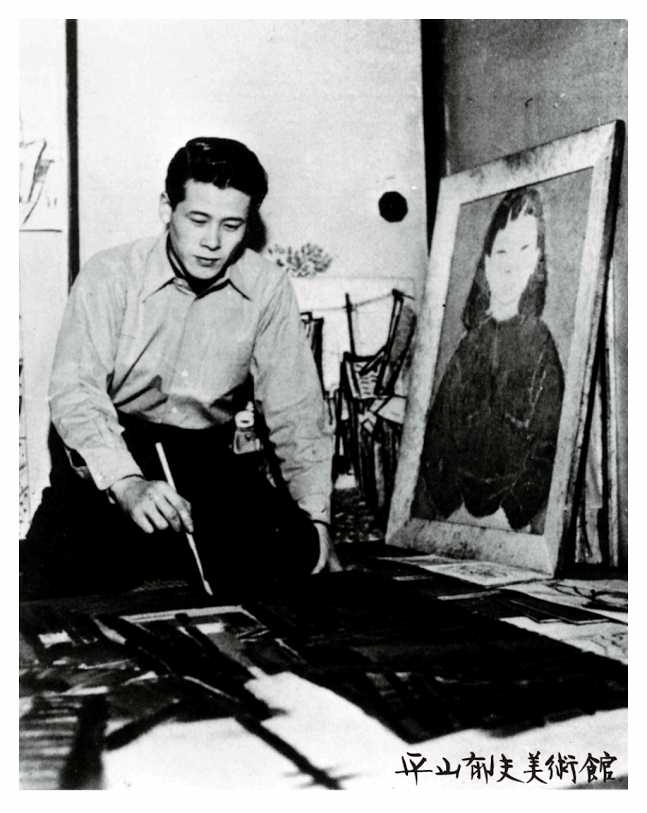

03. The road to becoming an authentic painter of Japanese-style paintings

When he was still a fourth-year student at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, Seison Maeda was seconded to the post of professor at the school, which later became the Department of Fine Arts of the Tokyo University of the Arts under the new system of education. After graduating, Hirayama started a career as a painter of Japanese-style paintings in earnest, working as a junior assistant under the direction of Seison Maeda. He entered the (In-ten) exhibition held by the Nihon Bijutsuin (Japan Arts Institute) for the first time in 1952 with a work in which he had confidence but the work was eliminated in the competition.

The work in question, entitled “Ieji (Homeward Bound),” is in the possession of the Hirayama Ikuo Museum of Art. Ikuo Hirayama later recounted that this rejection was a valuable experience for him as a painter.

He started painting a new work with the same name and composition, also called “Ieji (Homeward Bound)” on the same day he was apprised of the rejection and, in the following year, he entered the In-ten again with the work. (This “Ieji” is currently in the possession of the Hiroshima Prefectural Art Museum.) After that, he continued to win awards and became associate of the Nihon Bijutsuin (Japan Art Institute) in 1955.

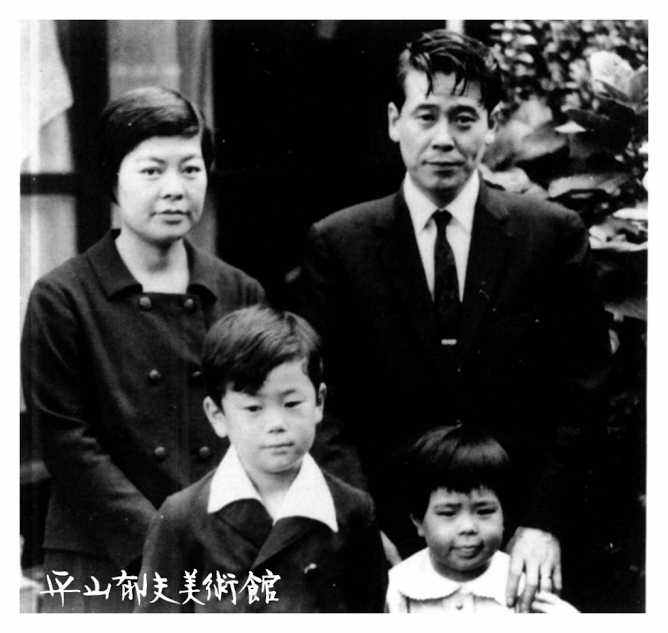

His works won awards one after the other at exhibitions, from the Nihon Bijutsuin Award (Taikan Award), to the Encouragement Award and the Minister of Education Award. His work was exempted from examination for admission in the In-ten in 1961 and he was recommended as a member of the Nihon Bijutsuin in 1964 at the young age of 34, establishing his position in the art world. During this period, he married Michiko Matsuyama in 1955 and had a son and a daughter.

04. Transmission of Buddhism

Around 1959 when Ikuo Hirayama was serving as an assistant at the Tokyo University of the Arts, he manifested symptoms seemingly related to radiation. He had suffered from the atomic bomb and his white blood cells count decreased to less than half the normal number. He intermittently suffered from extreme anemia.

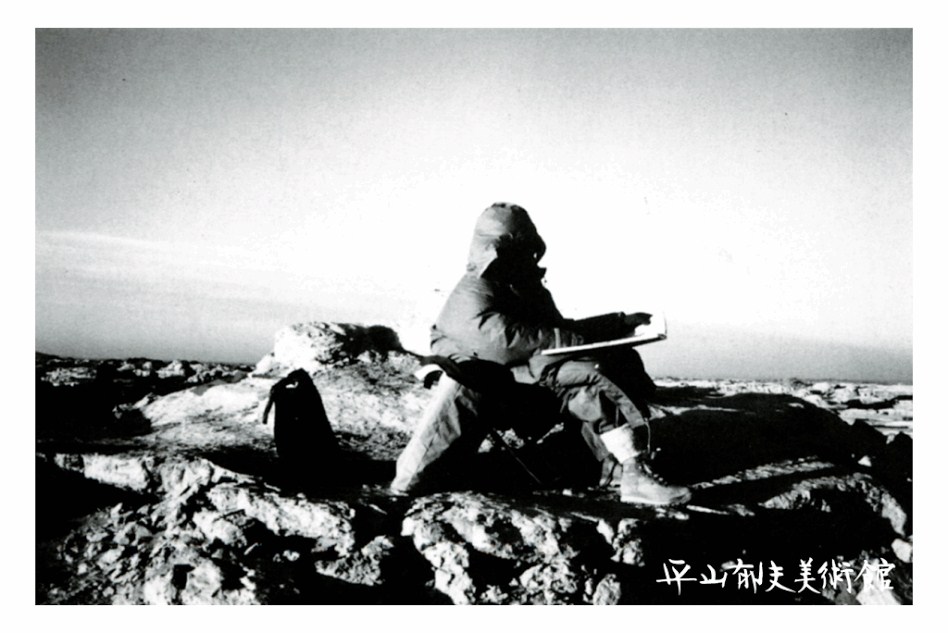

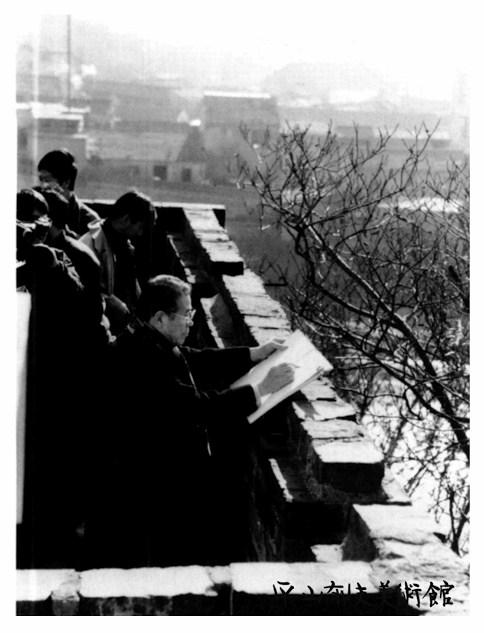

While Hirayama was confronting the fear of death, he went on a trip to do some sketching, bringing along students of his university. The trip was apparently like a forced march or mountain climbing through Mt. Hakkoda in Aomori. The fresh, shiny May green leaves may have reinvigorated the young painter, who once again felt his limits challenged.

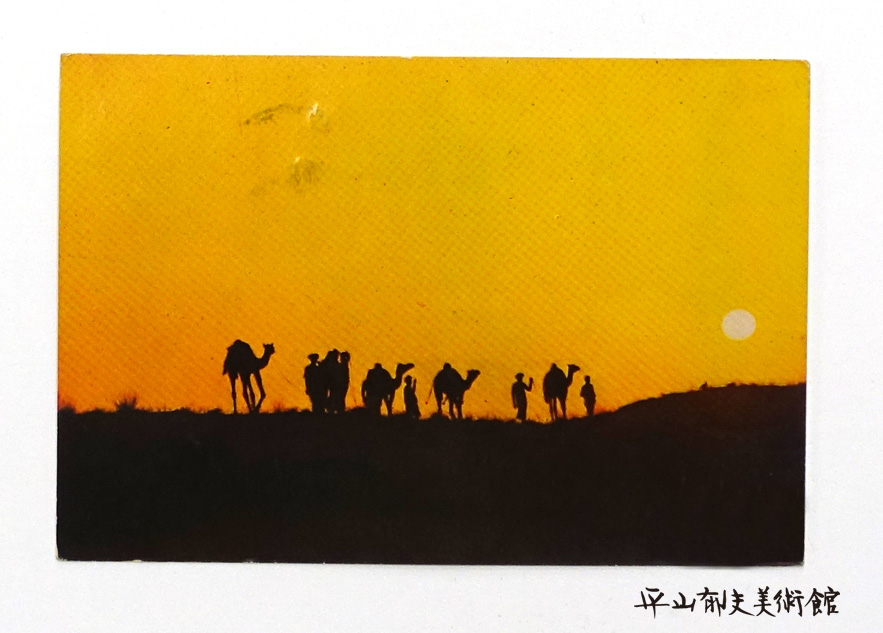

One day after his return from the trip, reading a small article in a newspaper proved to be a turning point for Hirayama. The article suggested the carrying of the Olympic torch for the Tokyo Olympic Games via the Silk Road and that inspired an idea for his painting.

He imagined a priest who travelled in the desert along the Silk Road finally arriving at an oasis. The painting was entitled “Transmission of Buddhism,” showing an image of the Chinese priest Xuanzhuang Tripitaka Fashi in the Tang Period seeking the teachings of Buddhism. It was exhibited in the In-ten, and a ceramic plate of the “Transmission of Buddhism” is now exhibited in the lobby of the Hirayama Ikuo Museum of Art. This is how a small newspaper article led to the birth of an original painting.

This work, born from his desire to “create a single work in prayer for peace,” was introduced in an In-ten newspaper review by art critic Michiaki Kawakita, and two lines of the review greatly encouraged Hirayama in his youth.

“Transmission of Buddhism” (which is in the possession of the Saku Municipal Museum of Modern Art) became his monumental work. It was also the starting point of a series of paintings as part of the “the life of Buddha” and a series of “Silk Road” paintings.

05. Contact with profound tradition of religious art in Europe

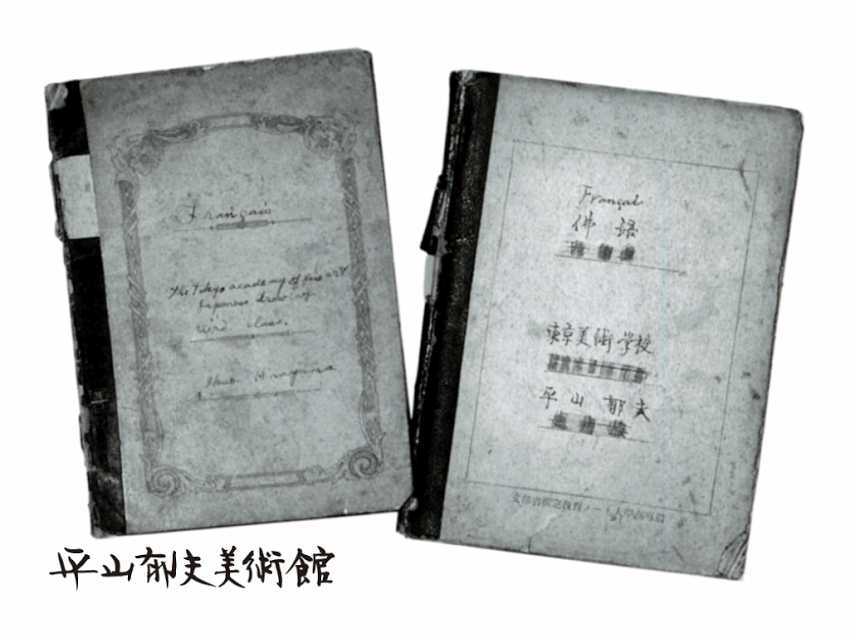

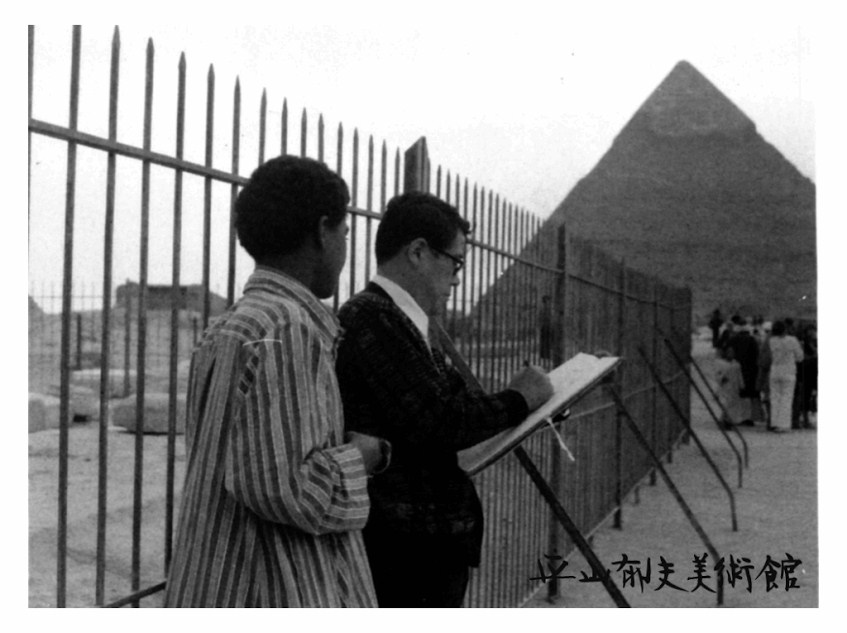

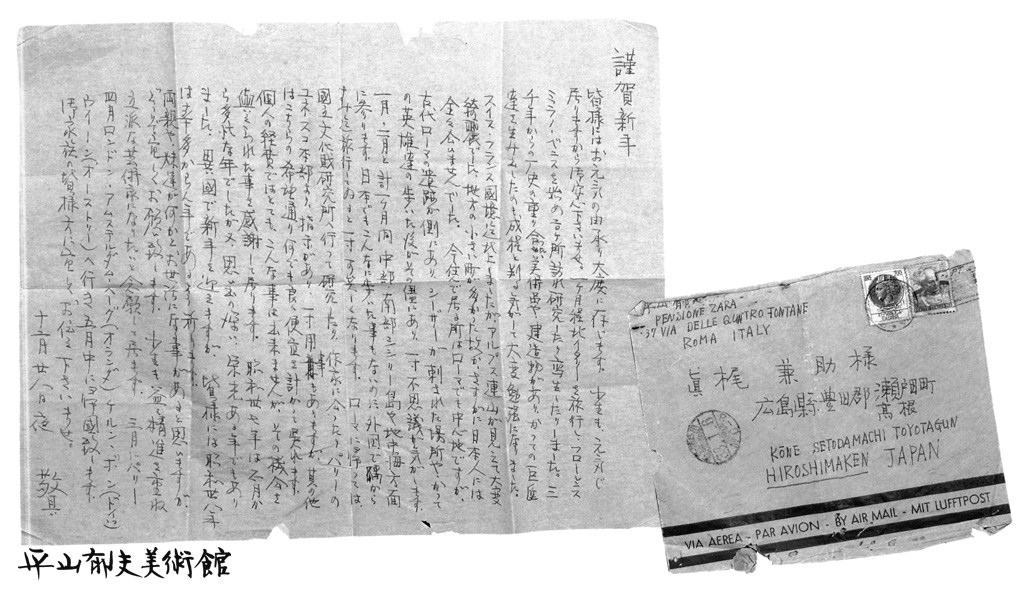

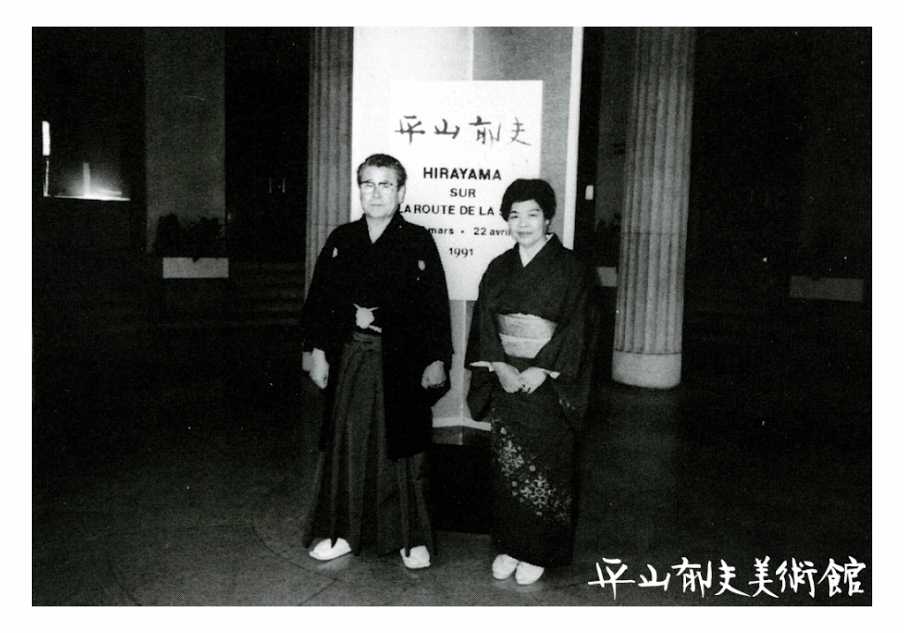

Ikuo Hirayama studied abroad in Europe for six months from 1962 under the first UNESCO fellowship.

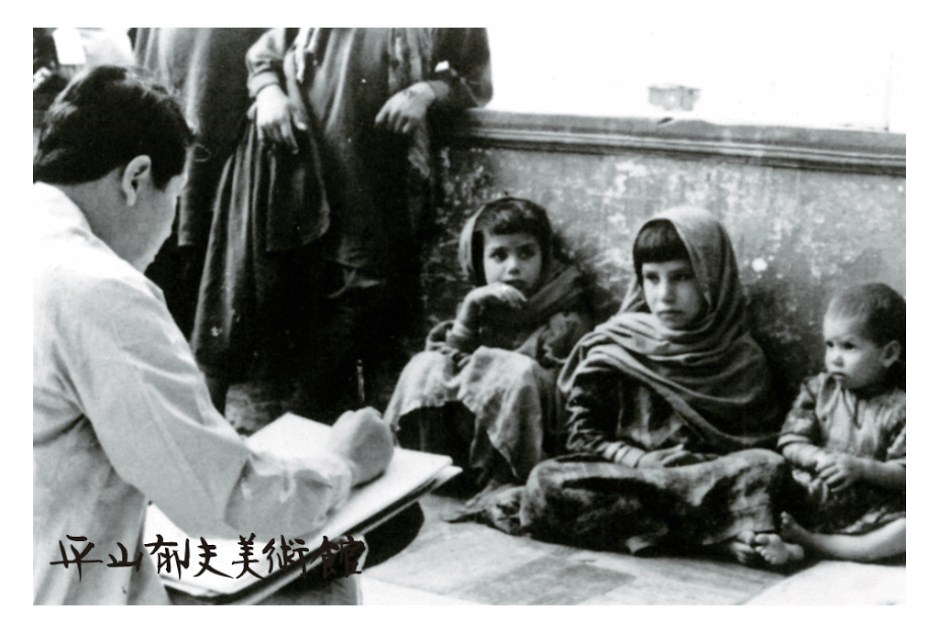

The subject of his study was “Comparison of Eastern and Western Religious Art” and he made a tour of five countries: Italy, France, the UK, the Netherlands and Germany. He visited churches almost every day in each country and made sketches of street views.

His contact with the tradition of religious art in Europe crystallized within him the idea that the future of Japanese-style paintings should be based on eastern traditions of India, the Silk Road and China, including Buddhism, just as western art is based on the Christian tradition.

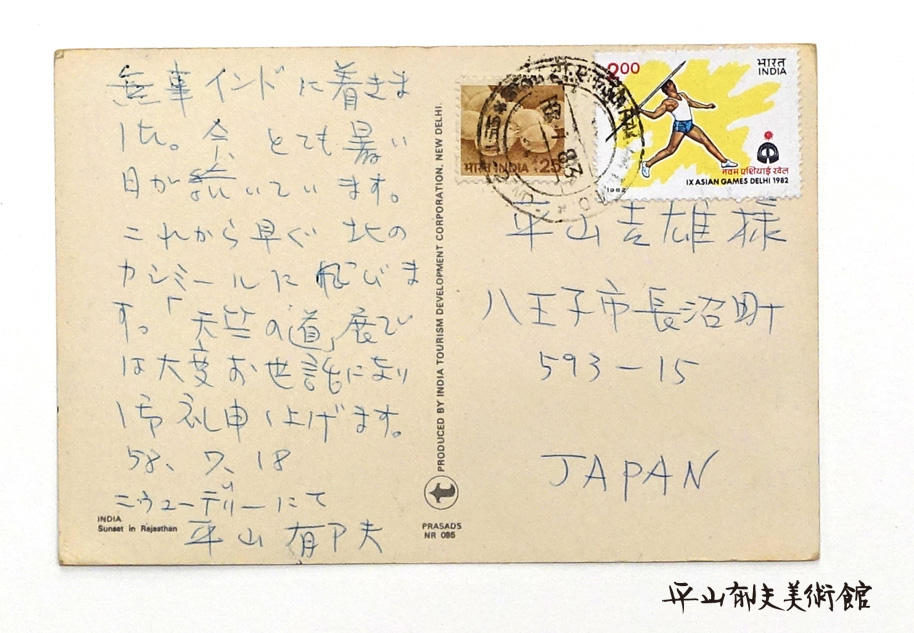

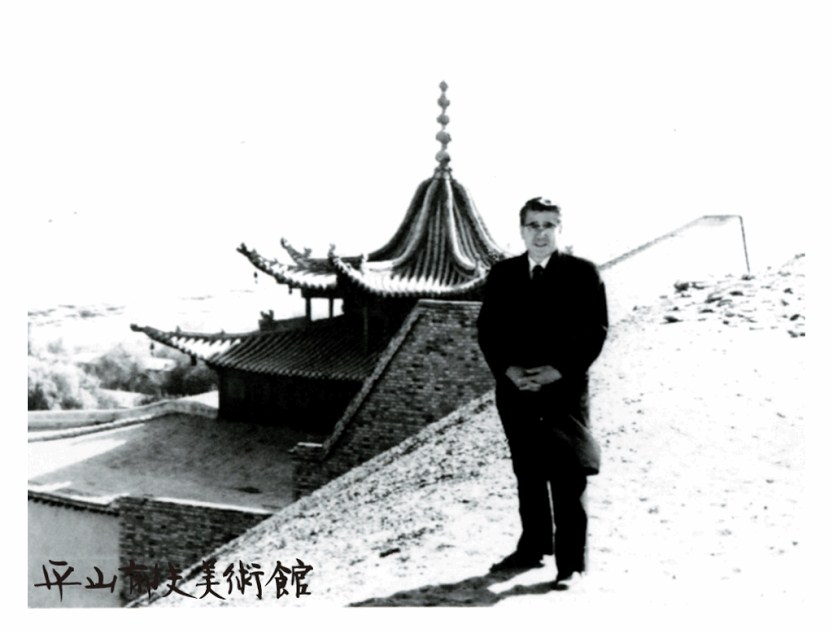

06. Journey into the origin of Japanese culture - Investigative trip to the Silk Road -

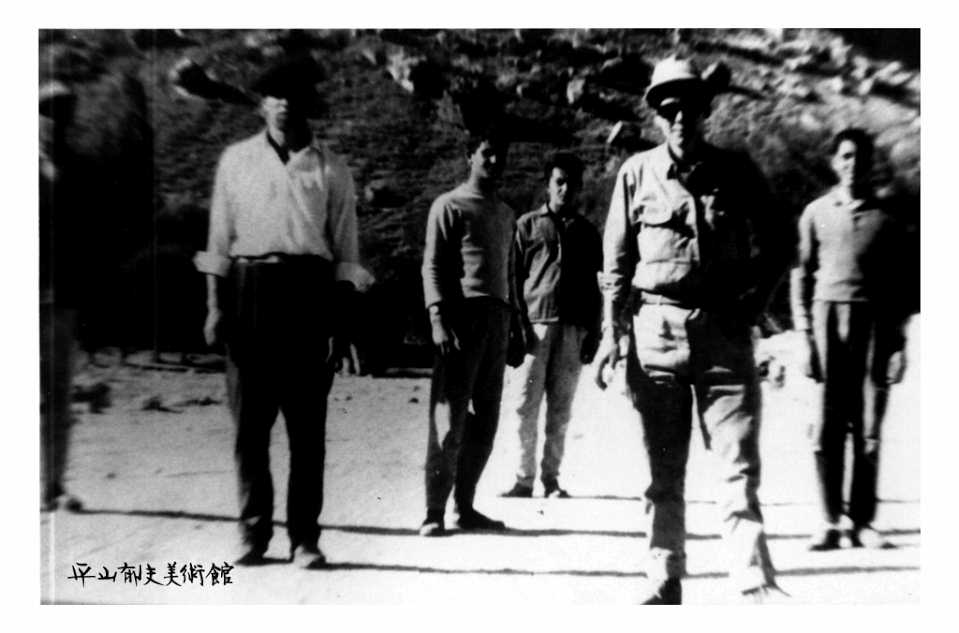

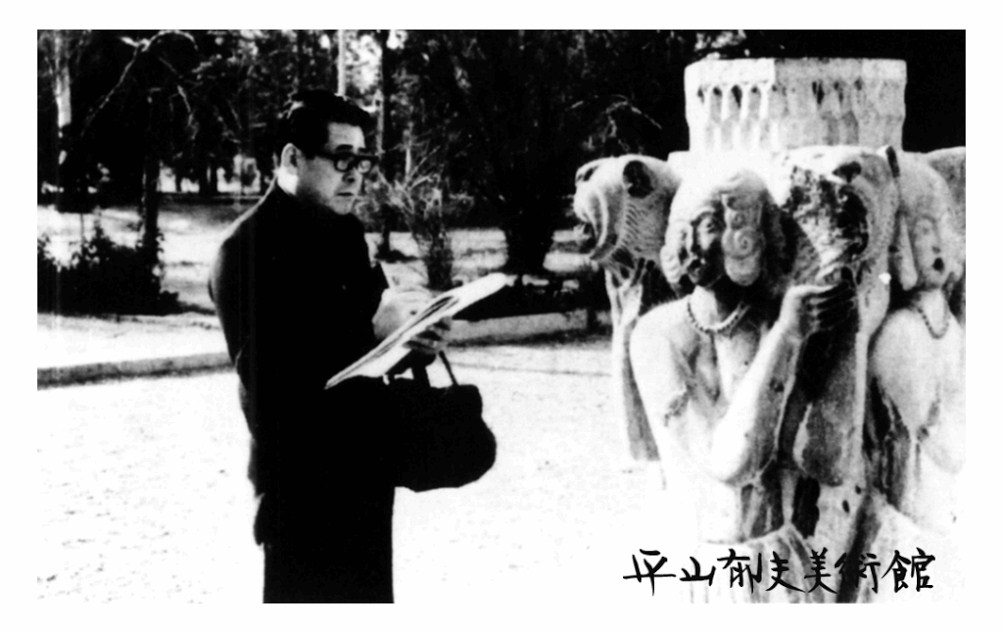

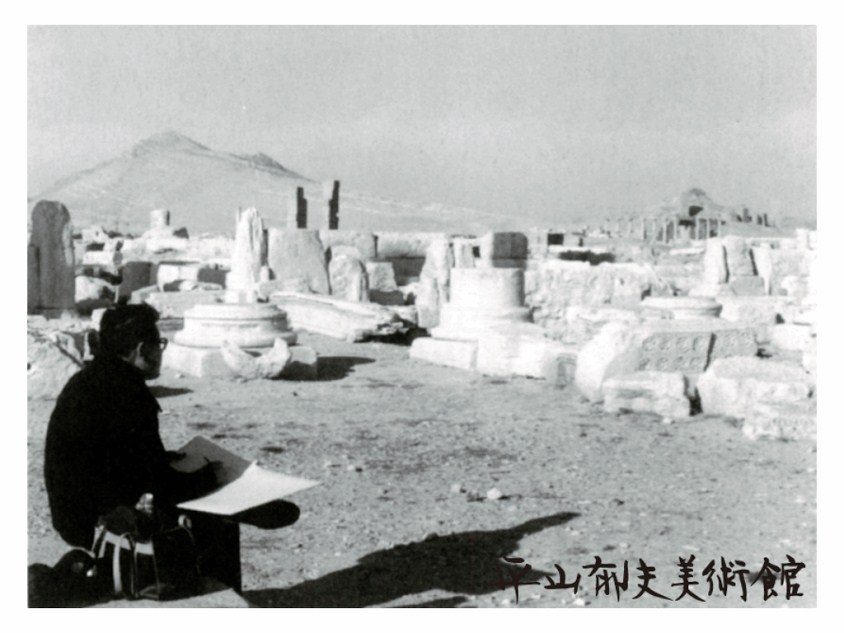

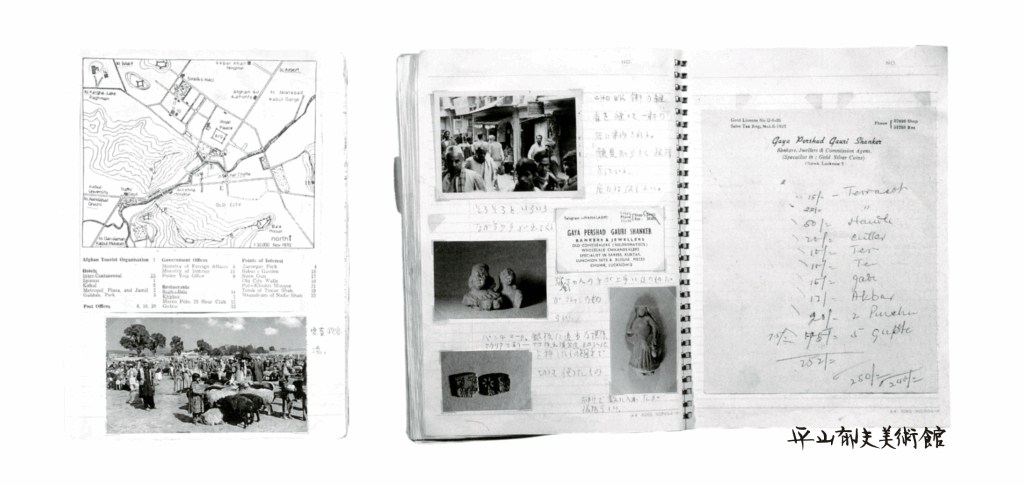

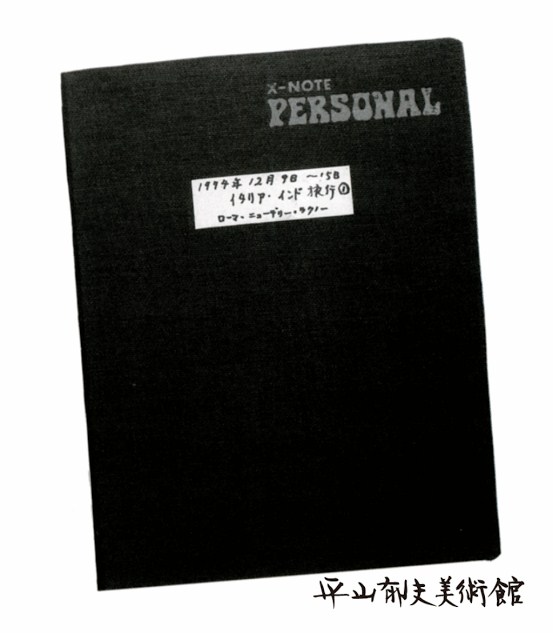

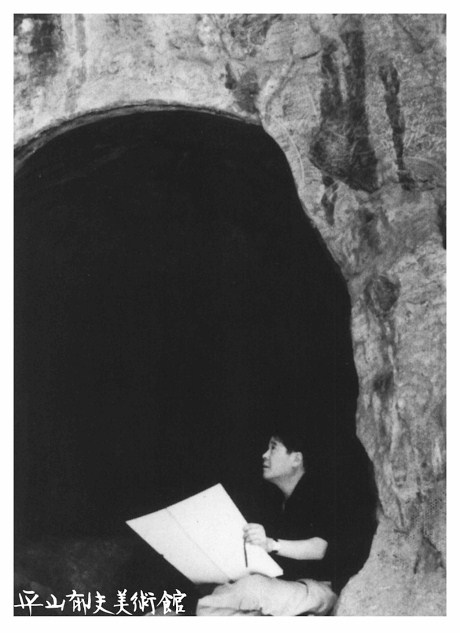

Hirayama participated in the first academic study group to the remains of the medieval Orient of the Tokyo University of the Arts and he was later involved in reproductions of wall paintings at a cave monastery in Cappadocia, Turkey. His first visit to the Islamic world was also his first encounter with a culture vastly different from that of Europe and Japan.

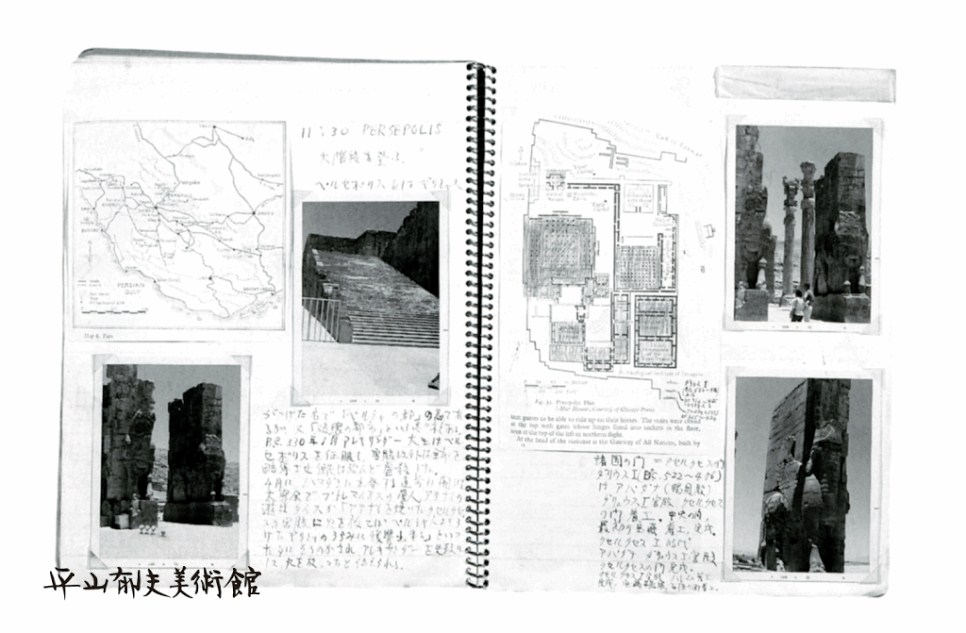

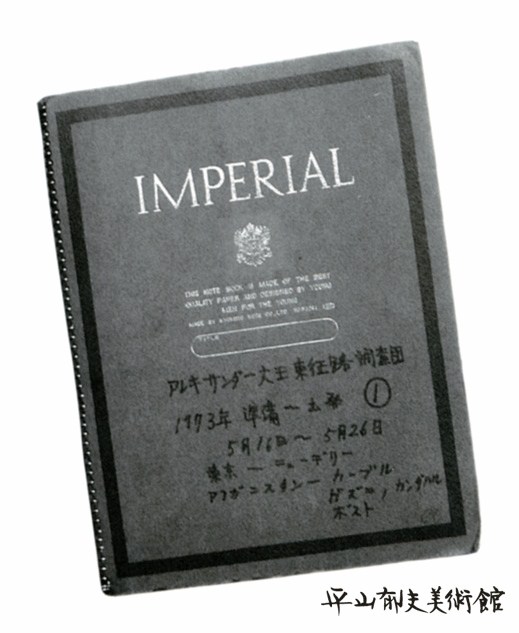

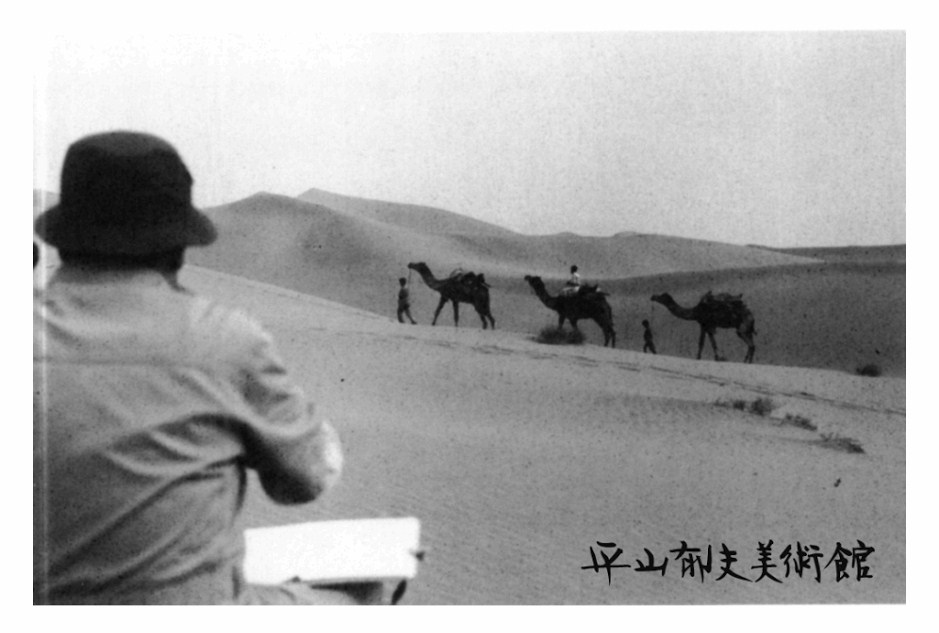

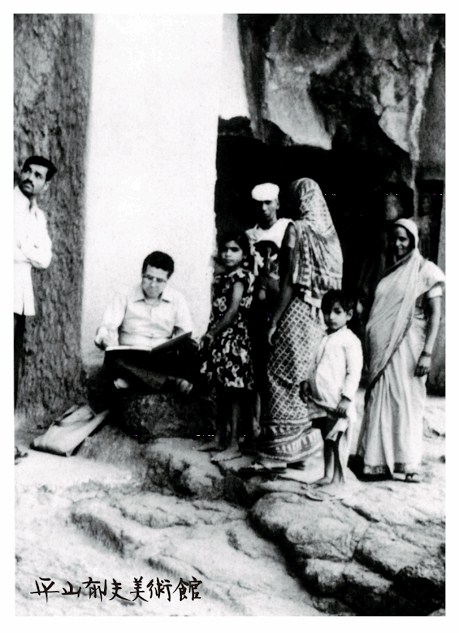

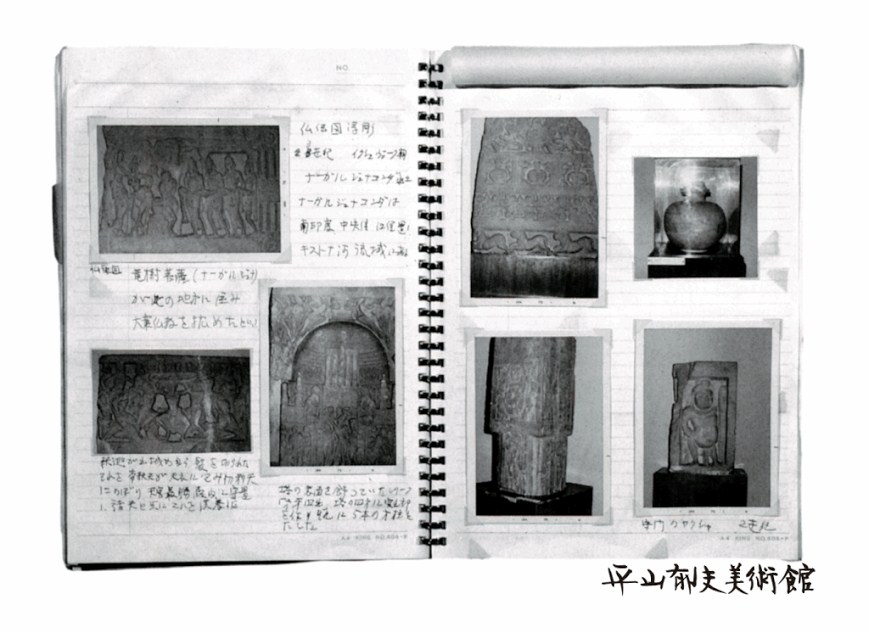

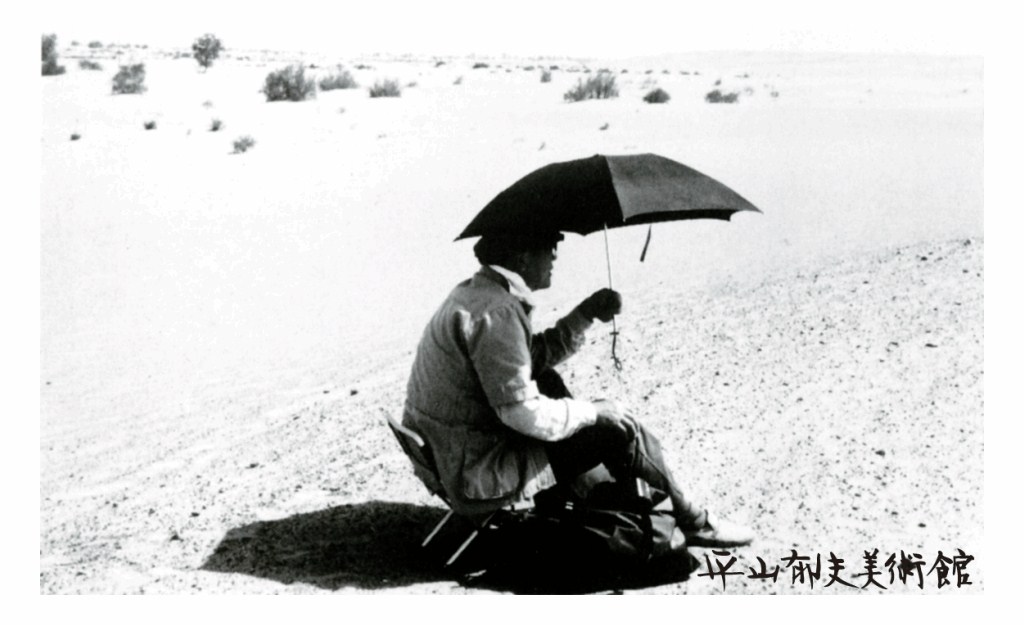

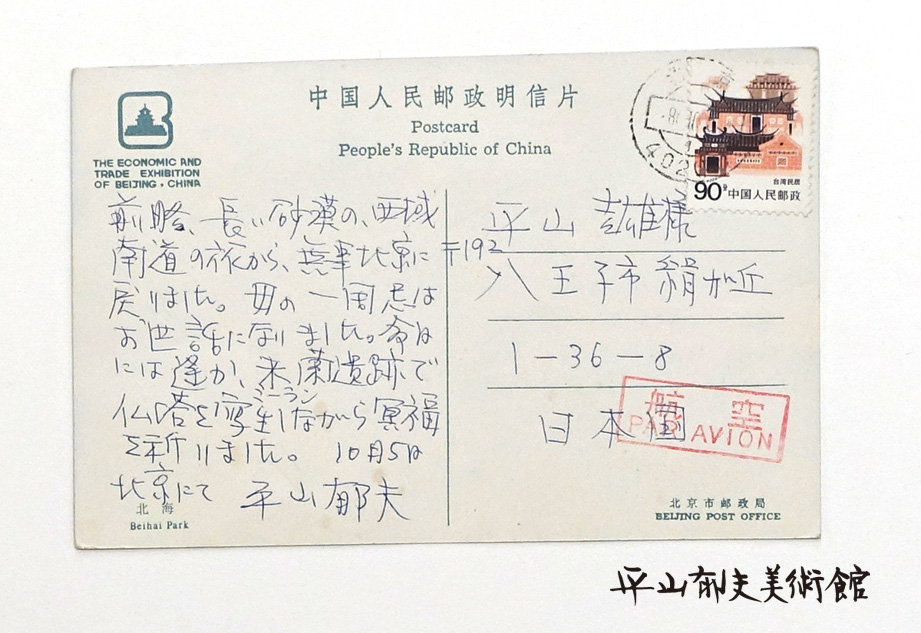

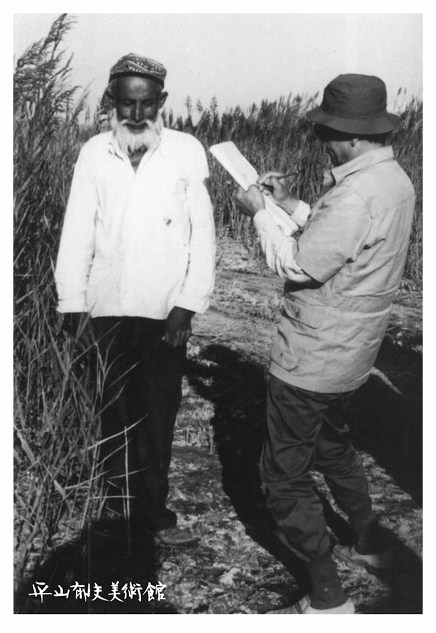

This first visit to the Orient became the starting point of a series of “Silk Road” paintings. After that, he took study trips more than 160 times to countries including countries in the Middle East, countries in the Central Asia, India and China, and the total distance of his trips reached four hundred thousand kilometers.

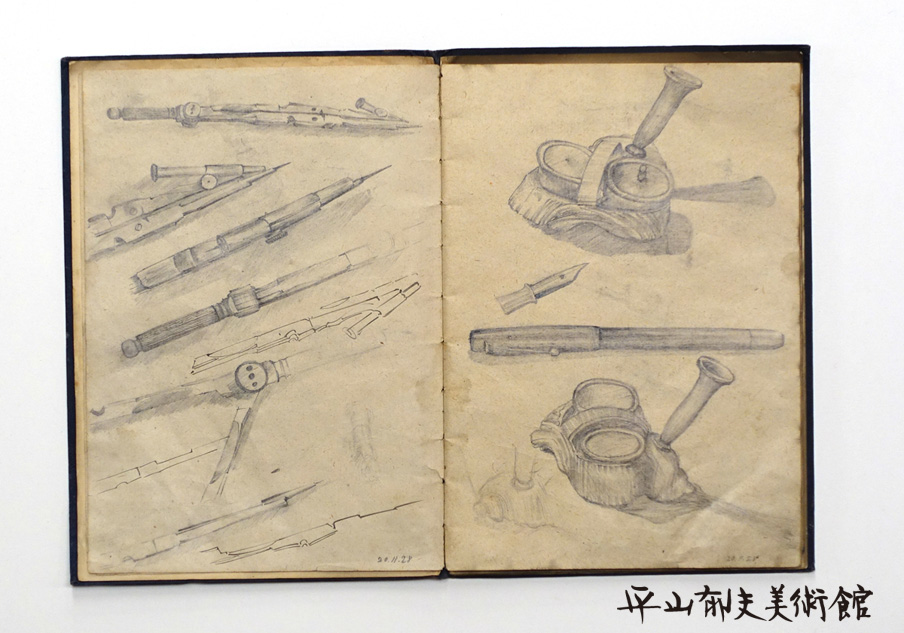

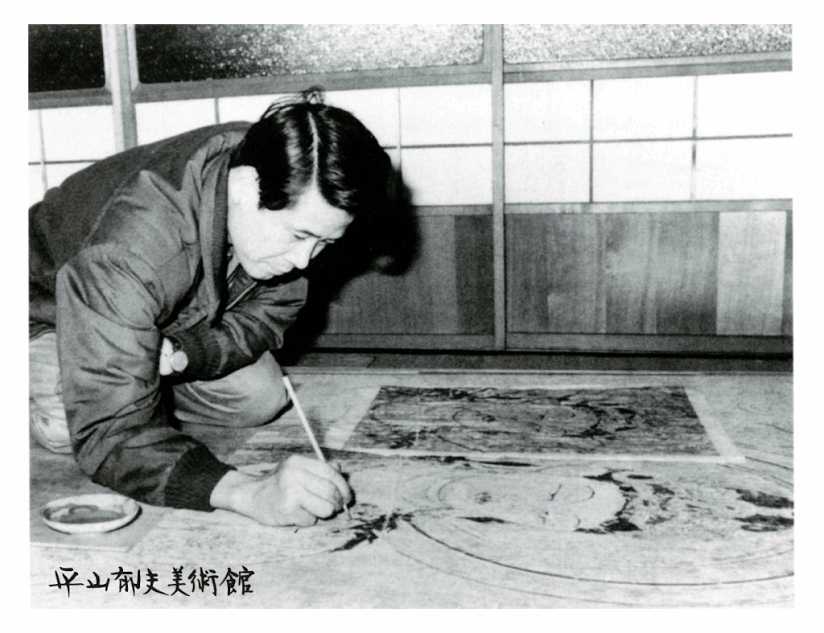

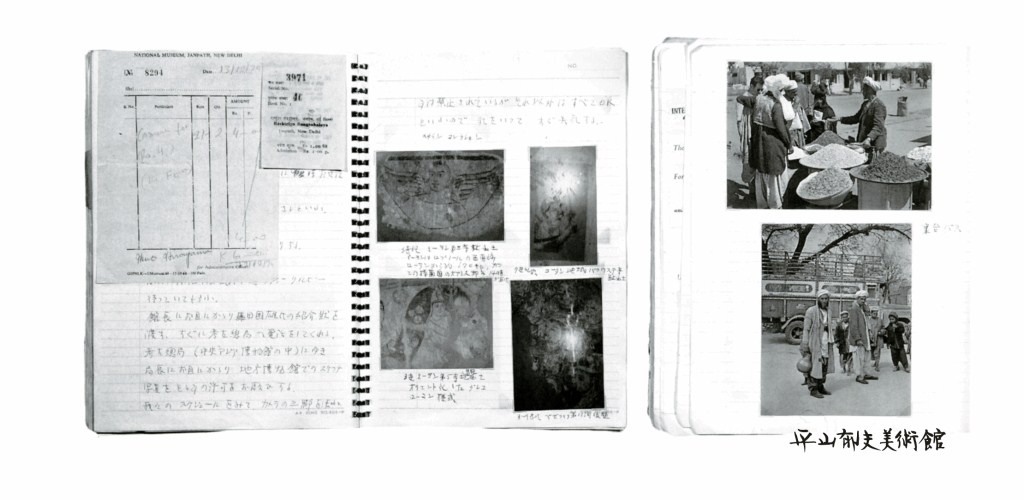

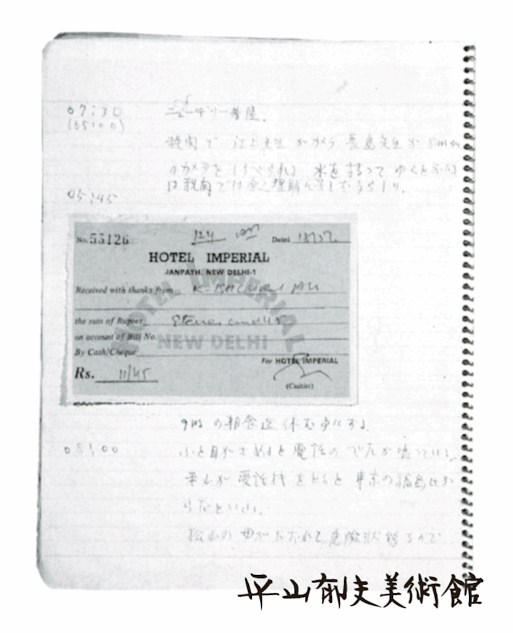

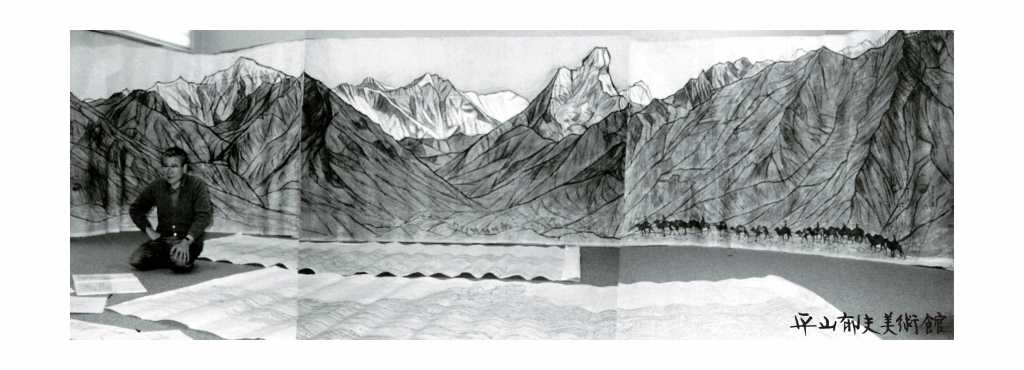

The number of sketchbooks he used during those trips reached almost 200 and the number of sketches he made exceeded 4,000. A large number of his works were created from this enormous number of sketches.

The jewel in the crown of those trips was an investigatory trip to the remains of Loulan located at the east end of the Taklamakan Desert in China. The Loulan Kingdom, which is said to have fallen in the fifth century, withered at the mercy of the harsh desert environment. The road along which Xuanzhuang Tripitaka once travelled marked the end of Hirayama’s thirty-year journey to try to trace Xuanzhuang Tripitaka’s footprints.

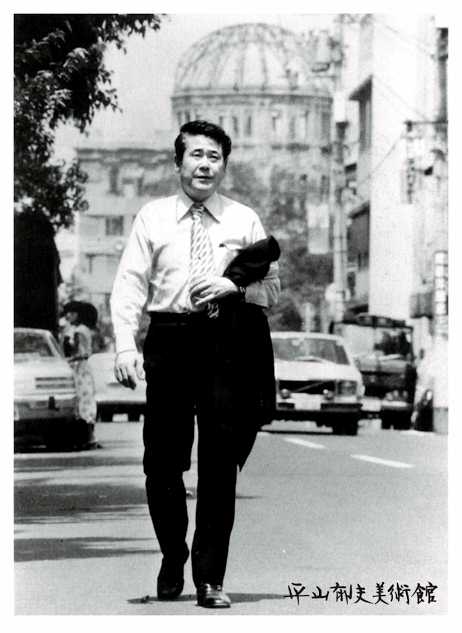

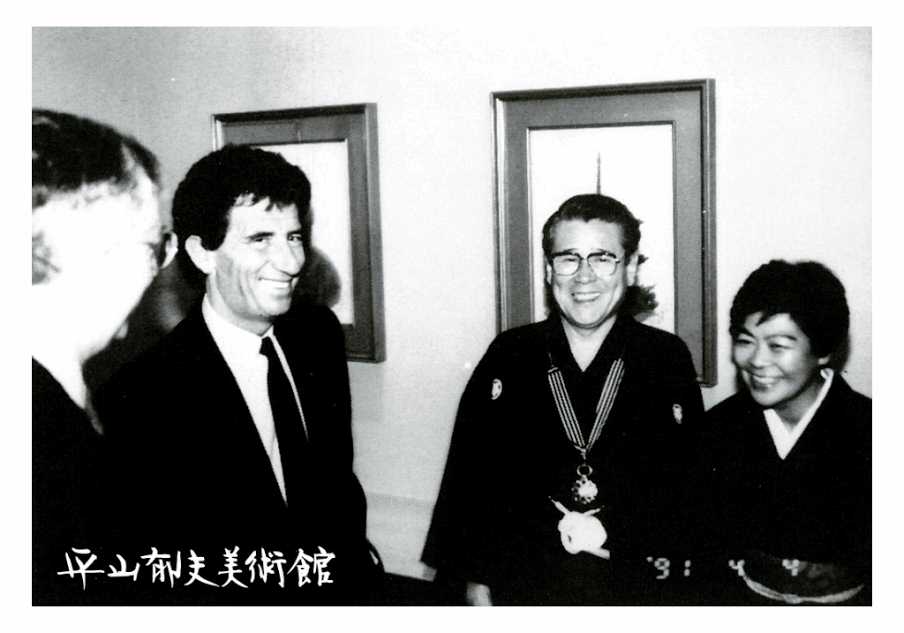

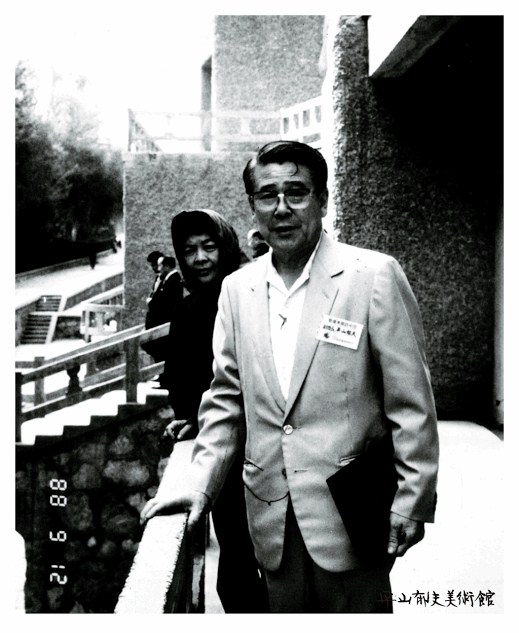

07. To the world - Non-governmental ambassador of culture

He continued to take investigatory trips to various places around the world every year after 1966 not only for investigations but also to play a role as a “non-governmental ambassador” to promote various types of cultural exchanges between Japan and the respective countries. For example, he visited Vatican City to donate a work “Lady Gracia Hosokawa” by his mentor Seison Maeda, and he bequeathed his work “Buddhist Missionaries to the Ancient East” to the modern religious arts collections of the Vatican. He also had meetings with very important persons many times for cultural exchanges between Japan and China, attended solo exhibitions held in foreign countries, invited overseas artists to Japan at his own expense, and established the “Hirayama Scholarship.”

In later years, he showed leadership as a UNESCO goodwill ambassador in charge of world heritage sites, etc. to promote World Heritage registration of an ancient tomb in Koguryo, North Korea, and to preserve the giant Buddhist statues of Bamiyan in Afghanistan though the latter unfortunately were destroyed.

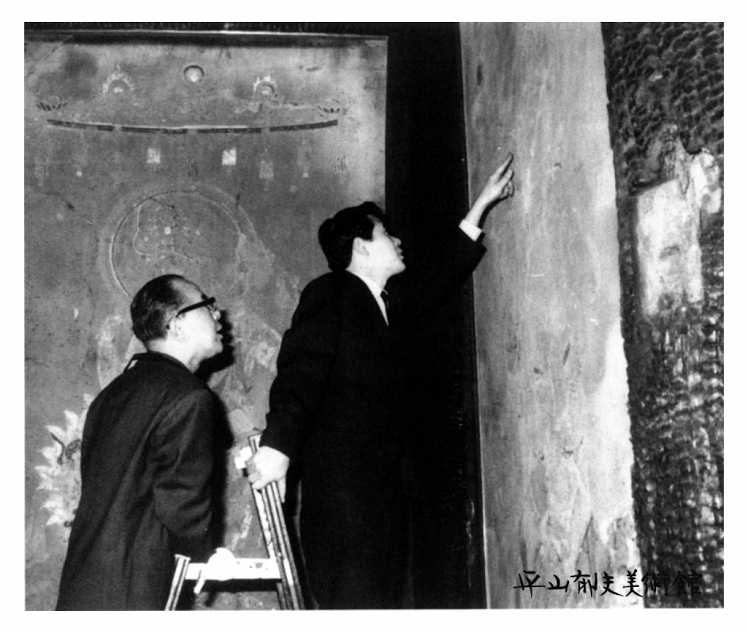

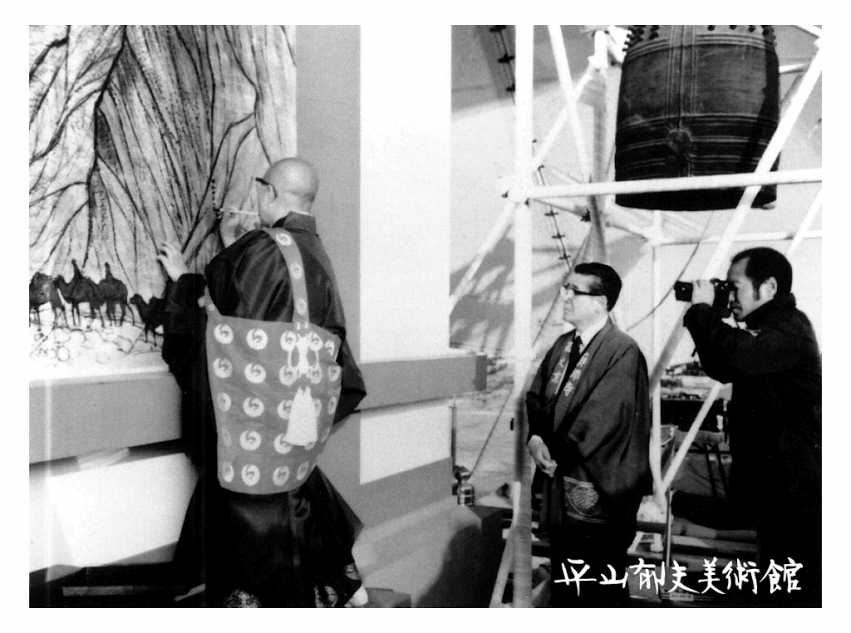

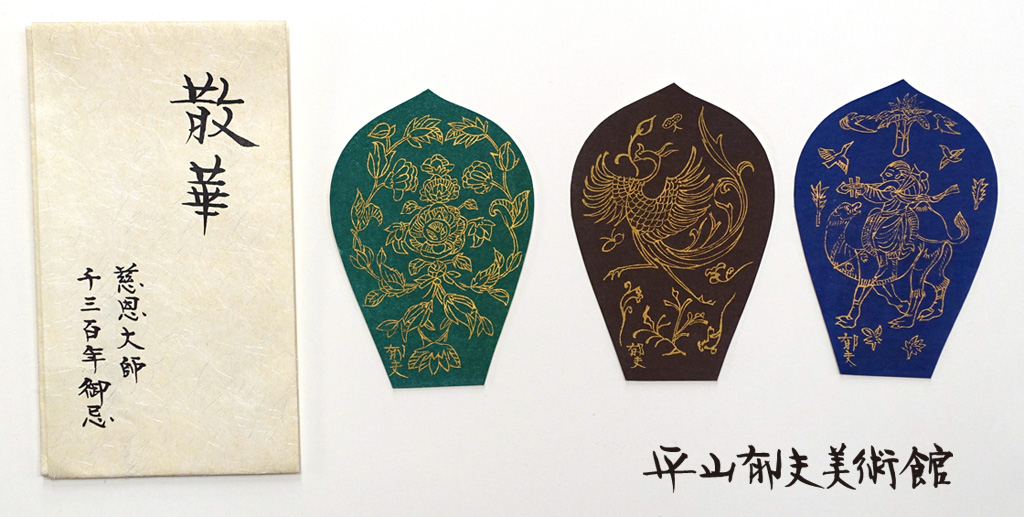

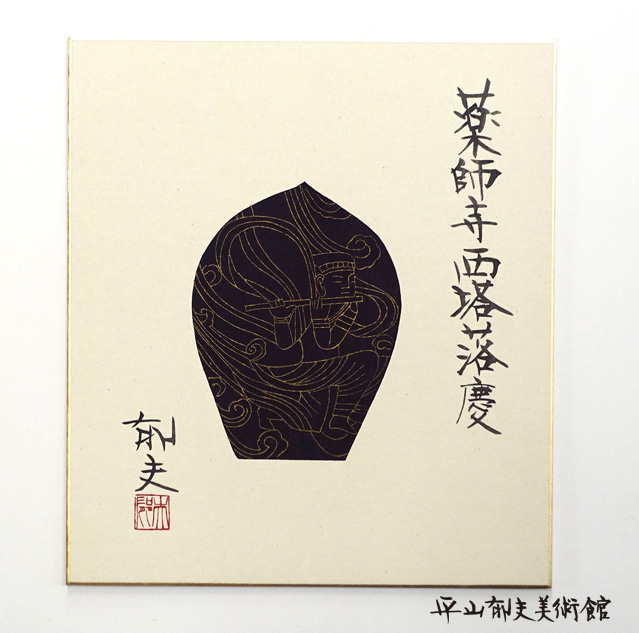

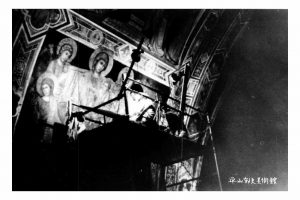

08. “Wall painting of the Great Tang of the Western Regions (The Great Adventure of Xuanzhuang Tripitaka)” in Xuanzhuang Tripitaka Hall of Yakushiji Temple

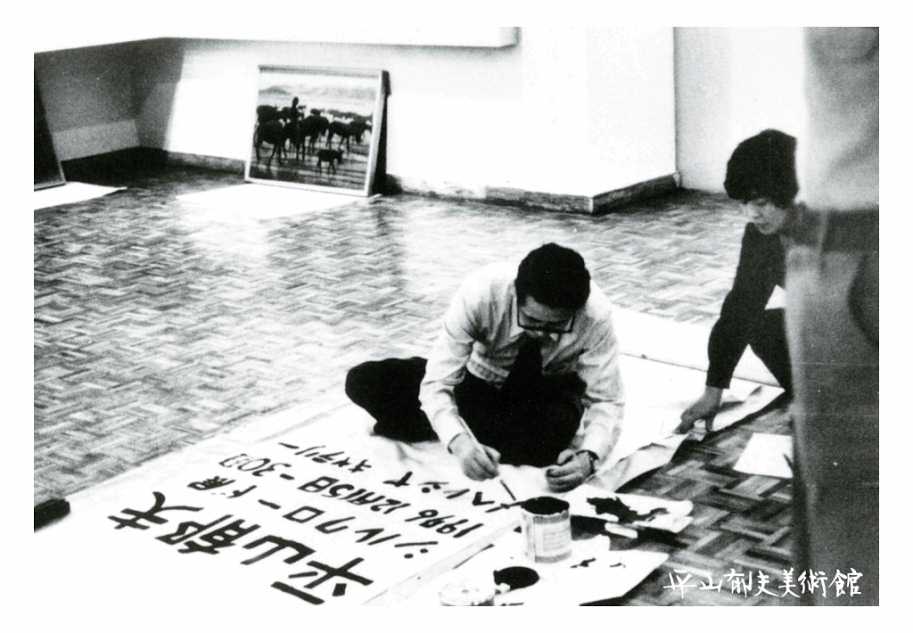

On May 13, 1980, a ceremony to commemorate the start of the wall painting of the Xuanzhuang Tripitaka Hall of the Yakushiji Temple in Nara and the opening of the Hirayama Ikuo Art Studio (in his house in Kamakura) was held.

Xuanzhuang Tripitaka, a Chinese high priest in the Tang Period who brought Buddhism to China in 645 after a 17 year journey to India was the inspiration for Ikuo Hirayama’s paintings on the subject of “Transmission of Buddhism.” The hall to which Ikuo Hirayama dedicated his wall painting was almost the same size as a small lecture hall. Constellations were painted on the ceiling and the “Great Tang of the Western Regions” consisting of seven scenes were painted on the wall to solemnize the achievements of Xuanzhuang Tripitaka. The large painting was 2.15 m in height and 50 m in width (including pillars) and dedicated on December 31, 2000 as a compilation of Ikuo Hirayama’s 30-year investigatory trips visiting the footprints of Xuanzhuang Tripitaka. The Hirayama Ikuo Museum of Art owns a large sketch of the same size as this wall painting.

09. Cultural activities and social contributions

Besides his paintings, etc, as the president of the Tokyo University of the Arts, Hirayama instructed younger painters (He assumed the position in December 1989, retiring in December 1995. He resumed service in 2001, retiring again in 2006.). He held important positions relating to international cultural exchanges such as UNESCO goodwill ambassador, chairperson of the Japan-China Friendship Association and chairperson of the various foundation for the promotion of arts studies for the promotion of cultural heritage preservation. He also continued energetic activities such as participation in lecture meetings and symposiums appealing for protection of cultural heritage sites etc. throughout the world.

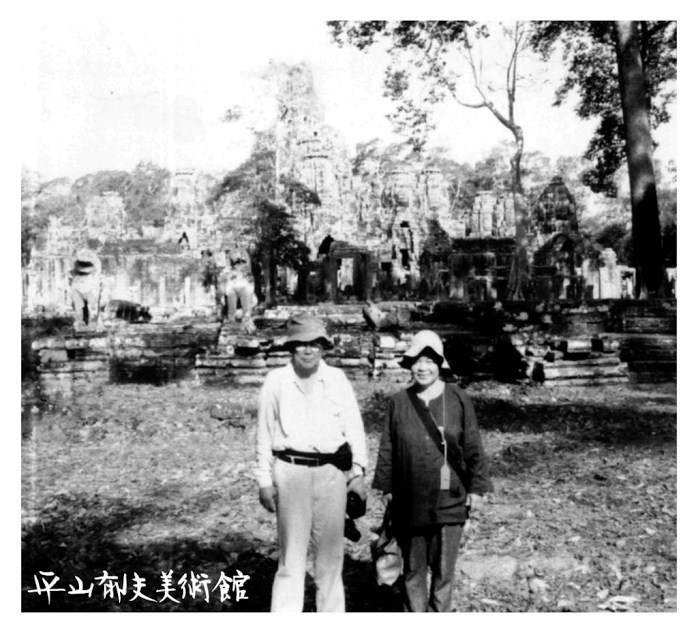

10. Red Cross plan for cultural heritage

Hirayama advocated the “Red Cross plan for cultural heritage” to protect and salvage cultural heritage sites etc., in the world currently on the brink of ruin. This is done, for example, through assistance for restoration of the Angkor Wat in Cambodia, the Buddhist remains in Dunhuang, China, the Nanjing city walls, and old works of Japanese art owned by major overseas museums, and he took the lead in the plan by putting forward his own money. He also played a leading role by, for example, holding exhibitions to raise funds.

“My belief that we should leave these treasures of cultural heritage for posterity with our own efforts is rooted in my desire for a peaceful world, the same theme that inspires my painting. Protecting the cultural heritage buildings etc. that remain, which essentially are surviving witnesses of history, is nothing less than an act of peace.” (“Nihonga no Kokoro (Heart of Japanese-style Paintings)” Kodansha) We know that inspiration for the above statement was probably Hirayama’s prayer for the repose of souls of his schoolmates who perished in Japan’s atomic bombings.